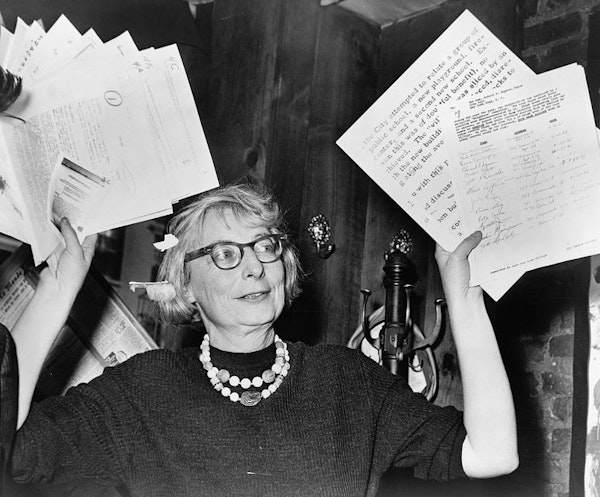

Jane Jacobs, 1961

‘The street works harder than any other part of downtown. It is the nervous system; it communicates the flavor, the feel, the sights. It is the major point of transaction and communication. Designing a dream city is easy; rebuilding a living one takes imagination.’ Thus spoke Jane Jacobs in her 1958 article, ‘Downtown is for The People’.

Three years later Jacobs would become famous for her ground-breaking book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She was talking about the threat of large-scale planning that was to wipe away whole neighbourhoods in the name of efficiency and productivity. This was, in her mind, the major threat that modernism posed to the contemporary city. Though platform urbanism has transformed this threat, the scale of the crisis is no less immense.

Jacobs feared that this chaotic but human landscape was under threat and would be lost forever in the rationalising schemes of planners who desired order rather than life. The war against the big developers and master plans has been, in the main, won. Now it seems that the main enemies of Jacobs’ Hudson Street Ballet are not knocking down neighbourhoods and replacing them with highways. Rather, the enemy is financialisation: turning the spaces of the city into instruments of capital.

And this new phase of urban transformation brings with it a new language. Having read their Jacobs, the new developers and neoliberal city officials speak the language of community to disguise their plans to make a killing. The Jacobs name is now frequently used by developers, urbanists, governments – and, more recently, technology start-ups – as a form of short-hand to signal metropolitan pleasures, when the true purpose can be something more venal. It has become increasingly prevalent to ‘Jane-wash’ a project with the promise of bike lanes, place-making, and walkability.

This is the kind of emergent urbanism that is simulated in developers’ videos used to advertise new projects. It is seen in the pixelated couples and children that fill up the supposed public space, displayed in their perfect interactions. The image is of the shockingly new, the earned luxury, but also of instant recognition. This is a place where you fit in: it recognises you for who you are. You belong here.

While taking on the image of the street ballet it forgets another one of Jacob’s key notions about what makes a neighbourhood. As she notes: ‘Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.’[1] It is not just what you do, but how you do it, and for whom it is done.

Container Park, Downtown Las Vegas, 2015

An example: In 2009, the CEO of Zappo.com, Tony Hsieh, bought 55 acre - 20 blocks - in Downtown Las Vegas, in order to test his theory of urbanism. Here he planned to build the ‘co-working capital of the world’ proving his calculation for why cities are such extraordinary centres of innovation. For Slate, this gamble aimed to produce “a seemingly paradoxical utopia: A new Silicon Valley just blocks from the Las Vegas strip.” Hsieh’s experiment is the most lauded example of start up urbanism.

On the surface, Hseih’s Downtown Project in Las Vegas appears to be a serious commitment to the Jacob’s ‘ballet of the street’. It presents all the latest notions of the city as a sustainable, walkable, spontaneously creative space, built out of the existing city. But this sales pitch should also send warning signals.

This liturgy of disruption was based on the notion that creativity is based on unexpected coming together – the serendipity of the street corner. This, however, was reduced to a meaningless calculus of ‘collisionability’. This is based on the speculation that innovation and economic growth spring from people bumping into each other. Thus the creative potential is reduced to an algorithm: a good city space has an average density of around 100 people per acre. In addition, it is estimated that each resident should then be Downtown for 3-4 hours a day. As a result, individual citizens should create about 1,000 “collisionable hours” a year. This also works in terms of space: therefore, one can reach 100,000 collisions per acre per year. This can be measured even more precisely to 2.3 “collisionable hours” per square foot per year. The corner is thus turned into a mathematical pattern.

This is clearly bullshit that satisfies a power point deck but means nothing in the real world. However, what it does suggest is that platform urbanism seeks the perfect urban code that can be replicated by whichever City Hall is willing to pay for the proprietary algorithm.

Comments