In 1969, William H. Whyte, the author and former editor of Fortune magazine, started a new job at the New York Planning Department. Previously, Whyte had made his name in the 1950s with a controversial bestseller, Organisation Man, which explored how post-war corporations had turned rugged individualists into homogenous suburbanites. He was also the first editor to encourage Jane Jacobs to write about the crisis of the city. As he entered his new role, he decided to conduct a series of experiments in the heart of the city.

Rather than assume that his office of planners, architects and transit specialists knew everything that there was to know about New York, Whyte discovered that once a project had been completed there were very few studies on whether the planning worked, or how people used these new spaces. Improvement was assumed because the planner knew best. Whyte subsequently hired a group of students from Hunter College, part of the City University of New York (CUNY), whom he stationed at various locations around the city. Their instructions were to watch how people came and went, how they used the city, how they conducted their ordinary urban lives. The results were a revelation.

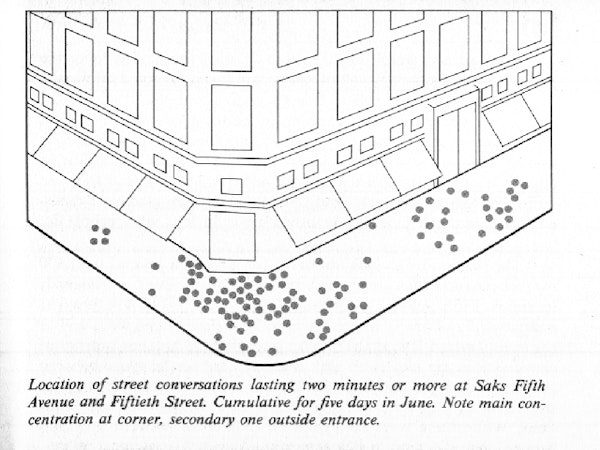

Take, for example, the results of the observations that Whyte’s students made on the street corner outside Saks Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. In the students’ illustration of the flow of human traffic over four days in summer, each dot represents a conversation, a moment when two people bumped into each other, stopped, and had a chat for longer than two minutes. According to this image, more often than not, conversations happened in the most inconvenient and unlikely places: many occurred just outside the front door of the store while the majority – some 57 percent – were conducted at the street corner; in effect these people were blocking the most congested place where other people were trying to cross the street, to turn, to move.

The momentary interactions that Whyte’s team observed were labelled ‘schmoozing’. ‘Schmoozing’ was placed next to ‘jaywalking’, and other informal ways of using the city. For Whyte, people rarely used the city in the ways intended. Instead they created their own public spaces, where they played out moments of intimacy and connection. The city is made of such unexpected moments of gentle chaos. It is this gentle chaos that Richard Sennett describes as ‘incomplete, errant, conflictual, non-linear’[1]. This is exactly the kind of behaviour that platform urbanism intends to design out.

Whyte’s study also highlights the difference between measurement and observation as means of understanding what is going on in the city. How do we measure such a concept as complex as a public space? Data is picked up by your bank cards, mobile phone, GPS, and face recognition software. Sensors, such as that developed by the Finnish Indoor Atlas, can map the interior of a building from the outside, promising that they will soon do for houses what Google Street View does for our streets.

Big Data collects lots of data but not all, it will therefore always be working with an incomplete set. Therefore, it must create an algorithm that makes predictions on the basis of means and calculated averages. Thus when a corporation pours over your data, they are looking at the agglomeration of averages that make up many but not all the choices, decisions and mishaps that mark your life. Thus Big Data is never more than a misted mirror, reflecting only a partial shadow of your complex self.

This raises some serious limitations to the potential for modelling the city. The challenges involved are evident in the increasingly complex nature of crowd simulation software, which needs to take into account to not only quantity flow and velocity but also irrational responses, randomness, and motivation. By contrast, observation encourages an appreciation of the complexity of the city beyond the numbers. The fact that we have the technology to do this job for us does not mean that it can achieve the same outcomes, or that it will tell us who we are, or predict how we should behave.

Study of Saks Fifth Avenue – William H. Whyte, Social Life of Small Social Spaces, Washington, DC: The Conservation Foundation, 1980

Comments