How does one protect oneself from the pervasive gaze of Platform Urbanism?

Perhaps, the first answer is: be rich. It was Edward Snowden who said: ‘Privacy is the right to a self.... Privacy is what gives you the ability to share with the world who you are on your own terms’.

But the ability to share, withhold, or take back private information is becoming increasingly difficult. Richard Clarke, the former White House security chief, announced in July 2014:

‘Over time, there will be fewer people who recall pre-Information Age privacy, more people who will have grown up with few expectations of privacy’. He later made it clear that future expectations for privacy would also be unequally distributed: ‘Privacy may then be a commodity that only the wealthy can acquire’

So privacy becomes a luxury that only the rich can afford. How does this affect the rights of the rest of us? On the one hand, we have ourselves to blame. Every time we sign up to a set of terms and conditions, we give to a corporation the right to mine our everyday lives for valuable information. Perhaps the question is not how can we protect our privacy, but how we camouflage ourselves in the pervasive public realm.

However, there are a number of different ways to camouflage:

1. Coloration

When an objects blends into its background. This is the most common form of camouflage seen across the animal kingdom and is most effective when the object is stationary. As the prey ‘disappears’ into the landscape, the sniper is hidden as they wait for their quarry, or artillery is covered over so to be undetected from aerial surveillance.

2. Transparency

The use of translucence or light refraction to ‘disappear’. In 2012 Mercedes Benz announced that they had created – using LED and cameras - an invisible car. The innovation, surprisingly, did not go away. Like something out of a Bond film perhaps, but also one of the most egregious examples of letting the geeks run the laboratory.

3. Mimesis

The uses of disguise, so that the object does not disappear but appears to be something that it is not. `such as a cuckoos egg in a host’s nest or mobile telephone mast designed to look like a tree. The first of these was developed in the 1990s by Larson Camouflage, who had previous built artificial landscapes in Disney World and the Bronx Zoo.

4. Disruption

Rather than blending into the background, disruptive camouflage break and confuse surfaces, making it hard for the object to be identified. This is particularly in use for objects in motion, what is sometimes called ‘edge detection,’ for example, the spots of a leopard, or the markings of a striped fish weaving in and out of coral. This is also the most common form of camouflage for infantry who are moving across afield. The British Army have used Disruptive Pattern material since the 1960s, firstly as a mixture of forest greens and browns; but this was adapted in the 1980s for the desert with beige, greys and sand.

5. Cryptic Behavior

This is used by both the predator and prey to ensure that the other does not detect movement. This can also include stillness and silence to blend and disguise position and avoid detection. This can also cover unexpected movements to disconcert and confuse the other. For example, many species of flies, move in a straight line towards a target in order to confuse.

Power through Platform Urbanism is ocular: it is a relationship between those who see and those who are seen. Under Platform Urbanism, the need to use camouflage is pervasive and urgent, and there have been many varieties of disguise developed and tested within the hyper-surveilled urban landscape.

The most pervasive and often effective is the hoodie, the uniform of urban youth who experience constant watching. This hooded sweatshirt, once used to keep athletes warm, can be simply pulled up to make facial recognition difficult. The use of drawstrings to reduce the dimensions of the face aperture are used for extra protection.

Except, the hoodie has taken on signifiers of class and race. In 2010, the British Prime Minister launched a policy to engage working class youth that was nicknamed ‘hug a hoodie’. After Trayvon Martin was murdered in 2012, while wearing a hoodie it became a symbol of the prejudice against young Black men, culminating in a ‘Million Hoodie March’ in New York.

Privacy activists argue that the ubiquitous monitoring by cameras, sensors and drones is a violation of human rights. In effect, the machinery of security has made us all insecure. They argue that individuals have a right to disguise their identity, mask their movements, and camouflage their urban lives.

Thorin Monohan, in his essay ‘A Right to Hide’ points out that an ‘aesthetic resistance’ has emerged:

‘A veritable artistic industry mushrooms from the perceived death of the social brought about by ubiquitous public surveillance: tribal or fractal face paint and hairstyles to confound face-recognition software, hoodies and scarves made with materials to block thermal emissions and evade tracking by drones, and hats that emit infrared light to blind camera lenses and prevent photographs or video tracking. Anti-surveillance camouflage of this sort flaunts the system, ostensibly allowing wearers to hide in plain sight—neither acquiescing to surveillance mandates nor becoming reclusive under their withering gaze.’

The use of masks is perhaps one obvious route, but these are illegal, as is hiding one’s face entering the vector of the surveillance camera. In 2014, the artist Leo Selvaggio, made a mask of his own face and started to wear it outdoors. In one exercise, called URME [You Are Me], he also encouraged others to wear the same mask – thus Leo Selvaggio swarmed the streets.

URME by Leo Selvaggio, source: http://leoselvaggio.com/urmesurveillance

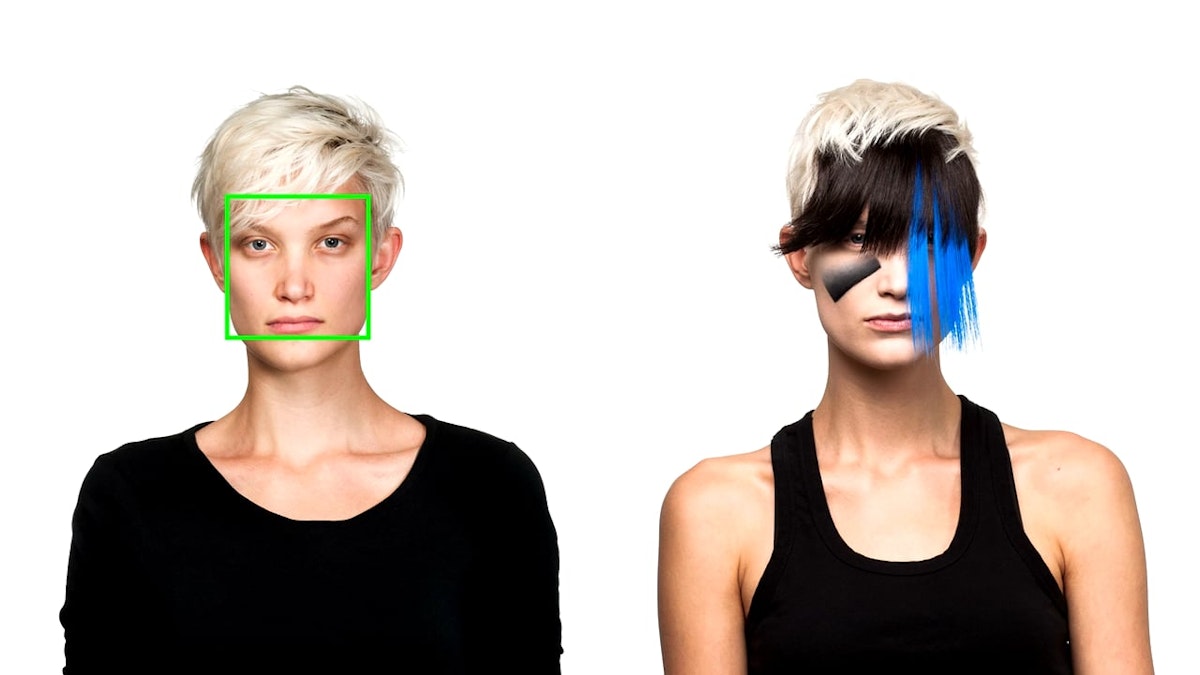

CV Dazzle was developed by Adam Harvey as part of a masters thesis in 2010. Inspired by naval camouflage during the first World War, it proposed to style hair and make up as a means to confuse facial recognition sensors. It does this by breaking up the surfaces of the face through shadowing, ‘tonal inversion’, and asymmetry. On his website Harvey offers a variety of looks including this one:

CV Dazzle look no. 5, source: https://cvdazzle.com/

However, as the software improves, can camouflage continue to combat these developments? According to Harvey, his experiment was conducted to challenge the viola-jones face detection algorithm. This is method devised by Paul Viola and Michael Jones in 2001 which function as a machining learning programme that searches for similarities and differences across the face’s topology. It is most effective with still images rather than an object in motion. Facial recognition software has evolved. Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) are based upon a multi-layered architecture of detection that ‘sees’ in a different way. Other forms of detection have become increasingly sophisticated: ears are unique and are increasingly being used as an identifier. Gait analysis attempts to identify individuals through their step patterns. Voice analysis and acoustic surveillance are also increasingly in use.

More than that, places are becoming increasingly policed against masks and coverings, so that the public has to be seen. In May 2019, an unnamed man was fined when he attempted to cover his face as he walked through an area that was being used by the Metropolitan police to test facial recognition software. The police were unapologetic:

‘The technology is being used in Romford as part of the Met’s ongoing efforts to reduce crime in the area, with a specific focus on tackling violence.’

Thus, camouflage is seen as a sign of guilt, in terms of the long-standing exhortation: why are you covering up, if you have nothing to hide? This argument obviously holds no water. You have nothing but yourself to preserve, for under surveillance capitalism your image and data has value within a transactional economy that you are not a part of. In the words of Hannah Arendt, you have the right to have rights that stand outside the market.

Comments