Platform urbanism is one reason why ‘logistics’ have moved to the centre of the debate on urban design again.[1]Geographer Deborah Cowen speaks about a ‘logistics revolution’ to define how the logistics of the physical circulation of commodities is growing in strategic importance for companies.[2] Whereas previously the notion of transportation was considered a necessity preceding or following production, nowadays the ‘logistics of the circulation of goods’ has become a dominant paradigm in the entire chain of production, distribution and especially consumption. This logistics revolution strongly affects the way that companies situate themselves within the urban territory. The success of platform companies relies not only on computerised inventory management and the forecasting of consumer behaviour, but also and especially on the location of spaces such as distribution centres, pick-up points and service desks. All of these spaces play a crucial role in accelerating the turnover of goods.

A well-known example is the rise of Amazon. Started as an online bookstore, the company now offers a wide range of commodities and services. Its strength resides both in its large assortment and in its capacity to deliver rapidly. Diminishing the time between buying and receiving goods is one of the main assets of platform businesses such as Amazon. It is here that the difference from the so-called brick-and-mortar stores is made. Paradoxically more brick and mortar are needed to achieve this aim of fast delivery: Amazon needs to situate distribution centres close to its customers. Like many other platform companies, it works with a combination of large distribution centres in the periphery of cities that complement small distribution centres, collection points, and service desks located in inner-city areas. The smallest of these nodes of platform commerce create new centralities within the historical city. The parcel collection point and the service desk seem to create new spaces of appearance and encounter in the contemporary city.

Platform logistics does not remain limited to the static occurrences of distribution centres, parcel collection points and service desks. A glance at contemporary cities illustrates the substantial ephemeral effects of platform commerce’s logistics: streets swarming with trucks, delivery vans and drivers on bikes, scooters and motorcycles, all of them trying to distribute a variety of products in the shortest possible time. Looking at the history of urban design, this is not a recent phenomenon. Until the late nineteenth century, streets were full of people selling, delivering and collecting goods. The street vendor, the house-by-house merchant, and the commercial traveller were only a few of the trader types that could be encountered on a nineteenth-century street. From this perspective, platform urbanism can also be seen as a return to the small-scale and individual commerce that increasingly disappeared following the emergence of supermarkets and shopping centres in the middle of the twentieth century.

Paradoxically, platform commerce’s small-scale and individual character is merely the visible aspect of what are often vast international corporations. The most crucial difference between the early twentieth and the twenty-first century seems to lie, however, in the importance of time. Never before has the rapid delivery of goods played such an important role. As a result, current platform logistics continue to re-calibrate urban space according to time and thereby increasingly render the city a ‘time-scape’.

For the many drivers, deliverers and couriers, but also for the majority of consumers receiving their products, contemporary cities have become, more than ever, geographies of time. Streets are no longer represented according to their name, offering or atmosphere, but rather as time sequences that all actors of the platform can strictly monitor. In other words, cities are increasingly conceptualised according to their temporal capacity to accommodate logistical flows. From this perspective, the algorithmic systems of platform commerce can be seen as constructing new urban representations in which it is not the longue durée but the courte durée of the city that forms the dominant paradigm. How these representations of temporal logistics influence our long-term attitudes to cities remains to be seen. However, there is no doubting that this influence will affect the way we conceive our future cities and neighbourhoods.

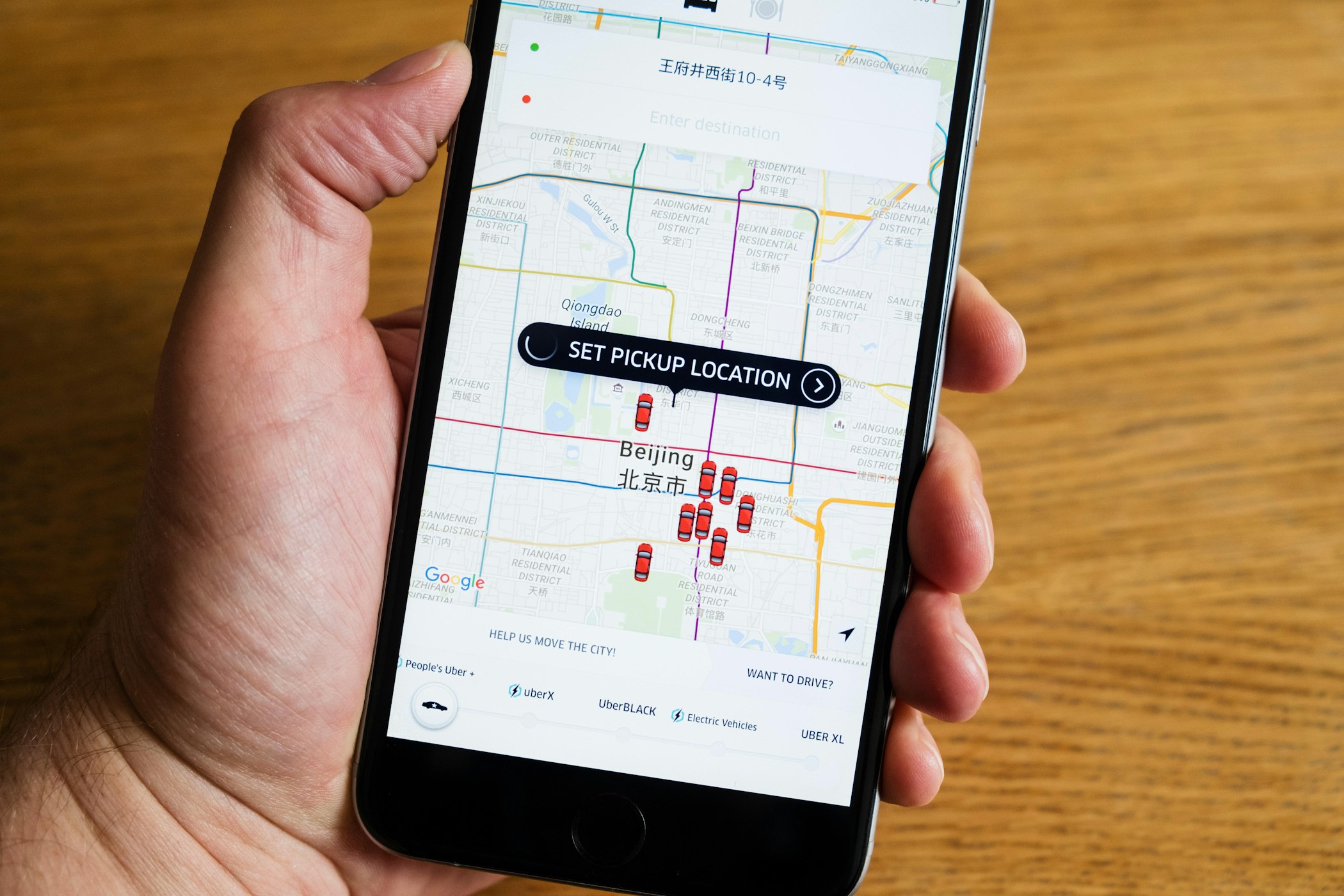

Iain Masterton, Alamy Stock Photo. Uber taxi booking app showing Beijing China on IPhone 6 smart phone. 7 July 2016.

Comments