No Wifi. May, 2020. ©Carle, Troy.

The foundation of the platform city is constant digital connectivity. This ethereal linkage[1] is provided by digital infrastructures: trans-continental and submarine, ocean-crossing fibre optic networks, data centres and regional telecommunication grids, cellular antenna sites providing blanket coverage in cities and along major transport corridors, and WiFi routers in the home or office. For those of us who rely on platform technologies, the availability of constant and uninterrupted cellular or WiFi signals is a given. It is expected that the digital services necessary for nearly all aspects of daily life are 'always on.' And yet, at the fringe of the greater metropolitan region, in the forests and fields far from the city centre, this service remains patchy and leads to new habits of connection as well as the inscription of these digitised, platformed services onto material space.

The advent of WiFi in the early 2000s signals the origins of this expectation of constant connectivity. As a way of finding WiFi in public spaces, individuals took to warchalking,[2] marking streets or walls with symbols to designate the presence of a wireless Internet access point. Of course, by the late 2000s and early 2010s the prevalence of smartphones and the digital infrastructure supporting these devices superseded this practice by facilitating a pocketable, 'always-on' Internet connection.

Nonetheless, the idea of providing a physical notation of the presence of an immaterial service remains useful in places with spotty, inconsistent coverage. When expectations of constant, mobile connectivity are upended in remote places, these sorts of street markings can still usefully indicate places providing online access. One place we find these phenomena is in Tuolumne County, located in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of Northern California, three hours drive east of the San Francisco Bay Area. Best known for its role in the Gold Rush in the mid-nineteenth century,[3] the county is located on the north-western edge of Yosemite National Park and composed of a patchwork of historic small towns and suburban developments linked together by two-lane highways. While some residents commute to the Central Valley's cities or into Silicon Valley, the local economy is composed of tourism, recreation and resource extraction (increasingly the area is also subject to massive wildfires).[4] Tourism is the most visible industry today, though logging retains a prominent place in the local economy,[5] providing lumber which is sold around the country. This area is for the most part not integrated into the platform city, but the desire for platformed technologies remains, even if this involves merely using a smartphone to send a text message, make a phone call or check email and social media.

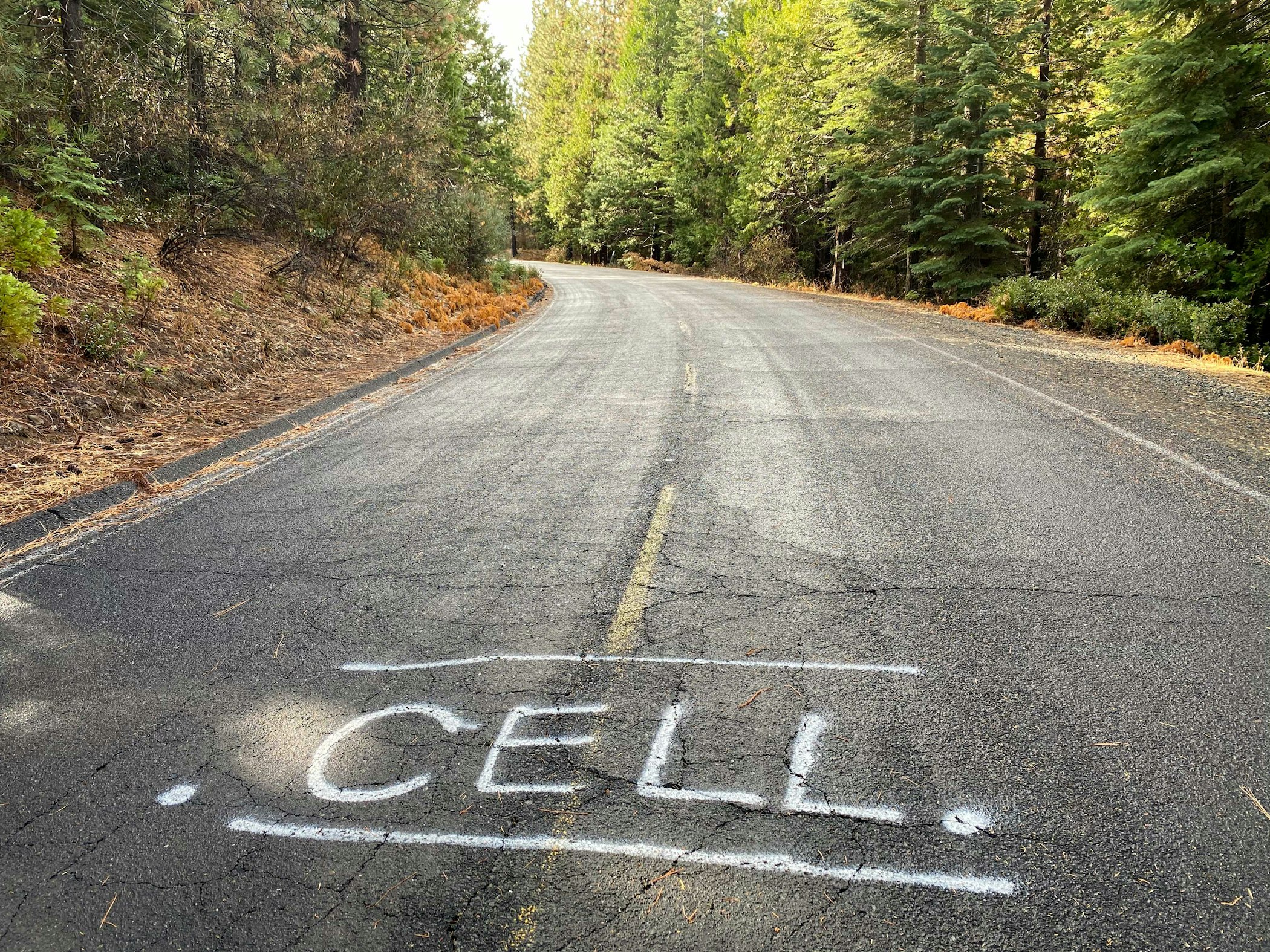

Cell. November, 2020. ©Carle, Troy.

For loggers and other travellers, Forest Route 3N01 connects Long Barn on Highway 108 to Cherry Lake and eventually Buck Meadows on Highway 120, offering access to more remote areas of the Stanislaus National Forest. [6]The sinuous road follows the contours of the landscape, passing in and out of hundreds of gullies, ravines, and over ridges with hairpin turns every few hundred yards. At two points on the road, closer to its northern terminus on Highway 108, someone – likely a logger – has spray-painted symbols on the asphalt to designate the presence of a cellular signal in an area otherwise without connection, one spot stating 'CELL' and the other marked with a WiFi symbol. At this link,[7] I've mapped Forest Route 3N01, the connection sites, and the cellular antenna using that most common of platform services, Google Maps, which would only function in this area if you were in one of these two locations of connectivity (or you had downloaded an offline map).

This is not the graffiti on a roadway marked by utility companies[8] to designate the underground presence of a water line or electrical conduit. These particular graffiti indicate a spot in the landscape where, by virtue of the topography, the folds of the terrain align with one of three cell phone towers in the area, on Duckwall Ridge, Mount Elizabeth, or Mount Lewis. Miles out in the woods, at two specific locations, loggers or other passers-by can stop for a few minutes and check their phones, plugging into their digital lives before returning to an analogue existence until they return to cellular coverage on the major highway routes. Far from the roads outfitted with Internet of Things sensor arrays to support autonomous cars,[9] this route still supports the extraction of lumber, a necessary commodity for the construction industry, even in the highly digitised platform city. The coverage noted by the graffiti drops off quickly, within a hundred meters or less. In the broader context of platform urbanism, these connected spots are uncommon and a far outlier. And yet this marginality prods us to recognise that platform technologies are unevenly distributed and not as widespread as we might expect. At the far edge of the metropolis, the demand for digital connection remains, even if the ability to connect is patchy at best.

This vignette was motivated by a conversation with Troy Carle of Twain Harte, California. His sharp eye first documented the painted symbols in May 2020, and after I received the invitation to contribute to the Platform Urbanism book, at my request Troy returned to the site to document the location in November 2020. Photographs are provided by Troy.

Comments