As something beyond physical awareness for the major part of urban population, and partially ill-conceived as urban hinterland, the oceans seem to play a minor part in our domestic lives. Besides an overall raising awareness of plastic pollutions, and wide understanding of the ocean's impact on terrestrial climate, and the endangering of species – all of which we conceive as very distant events either in space or time – access to underlying mechanisms by which the oceans are managed, is available only for those who are environmentally aware, and in search of it. Instead of depictions of faraway places in photographs, here it is through maps and diagrams that distinct spatial concepts are rendered. Online platforms might actively aid this process, in their capacity to suggest future sanctuary sites on various environmental platforms, or the ways in which they offer the means to find information about how we can take part in oceanic concerns by making use of fish-catch tracking services.

In its liquid state, the widely communicating water-bodies and migrating species throughout, the ocean challenges our land-based concepts of spatial management. Entangled with problematics of responsibility and governance – arising from zoning and the allocation of sovereignty over certain portions of the seas – our trained stationary understanding of space largely refuses to correspond to possibly adequate representations and descriptions of the ocean’s inherent characteristics.

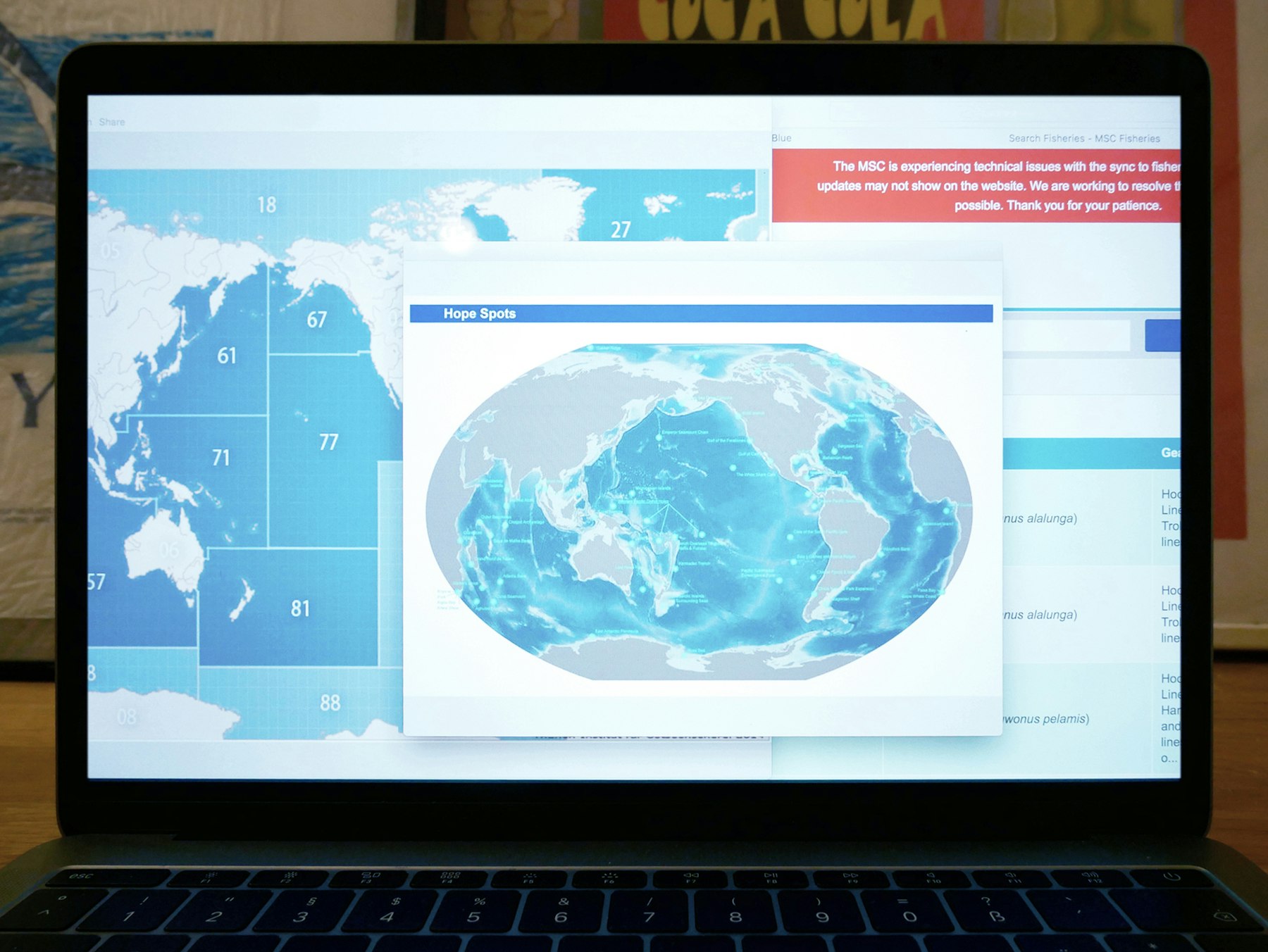

The complex coding that can be found on seafood products suggest the possibility of referring back to its spatial origin. With an emphasis on locality rather than on space, the indexed information merely depicts abstract zones that do not necessarily correspond to named geographic regions. Whereas on land we assume certain properties as firm and distinct – at least with regard to its observed unchangeability – the oceans seemingly do not offer such conditions. Here, specific difficulties arise when designation standards of marine protection areas are to be assigned to international waters, or regions that are rather characterised by fluid features. As convincing as a world map may be in indicating sanctuary sites with tiny dots, it can make us aware of small vulnerable places in the midst of the seas, it becomes difficult when further specifications of these places need to cope with both legislation and cultural affinity. Whereas imaginary naming of ocean areas (White Shark Café, Western Pacific Donut Hole 1-4, Gardens of the Queen, Cocos-Galápagos Swimway) comply with the latter, adequate descriptions of their physical features that suffice for the former seems more difficult. Derived from terrestrial conditions, potential ocean heritage sites have to correspond to legislation requirements that create paradoxes in feasibility: as identification, accessibility, monitoring and coordinated management are perquisites to the listing of a site, its extension, discreteness and degree of remoteness must also allow for this. For the high seas, and especially international waters or for areas characterised merely, though unambiguously by dynamic features such as current fronts, these constraints pose great difficulties, since neither clear or even fixed boundaries can be defined, nor can accessibility be guaranteed.

As much as temporal but persistent or recurring site features can be grasped in verbal description, attempts to delineate fix physical boundaries seem implausible. And even if we are able to point to certain places on a map, the corresponding spaces still remain distant and largely inaccessible.

Collectively compiled Hope Spots as potential ocean sanctuary sites; Mission Blue Sylvia Earle Alliance / Suggested coding for fishing areas based on FOA by the Thünen Institut für Osteefischerei / MSC Marine Stewardship Council - Fish Tracking.

Comments