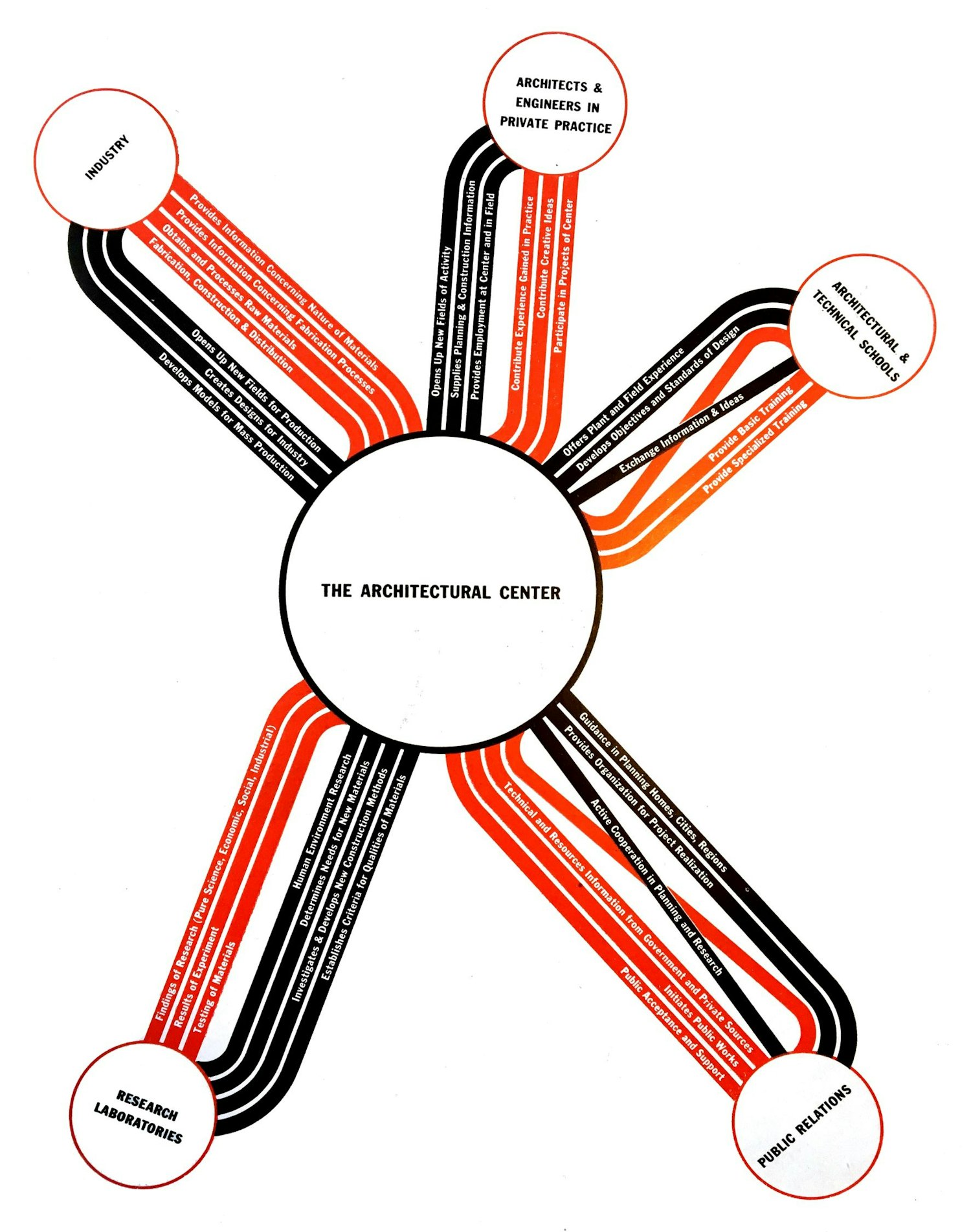

Lawrence A. Kocher & Howard Dearstyne, 'Diagram for the Architectural Center: an organization to coordinate building research, planning, design, and construction.' New Pencil Points, July 1943, p. 27. Photo Taken: Hagley Library, Wilmington (Delaware), USA. Archive of the American Iron and Steel Institute. 2017.

John Gibbons (photo). 'Incomplete Border Wall South of Campo.' San Diego Union-Tribune. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/opinion/editorials/story/2020-07-02/trump-border-wall-kumeyaay-burial-grounds-protests. 2017.

I wonder how the Internet, as another structure of control whose primary purpose is to make corporations money, is at all helpful in building movements. … The Internet is the ultimate Cartesian expression of mind and mind only. There are no bodies on the Internet. There is no land.

— Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg)

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson states there are no bodies on the internet; that is has no land.[1] But what is the body of the internet, or of offspring like 'platform urbanism'? If the Internet as we know it has 'no land,' it does not mean it is not grounded. As Simpson notes, it is grounded in corporate monopoly power – a notoriously mystifying concept. But the history of corporate monopoly is full of attempts at representation. In fact, we might argue that its ultimate hegemony comes from its ability to represent itself in particular ways, thus elevating some forms of existence over others.

As I write this, for example, just a few miles from my office at the University of California, San Diego, the United States Border Patrol is violently evacuating a Kumeyaay Nation protest camp against Trump’s border wall, which is being constructed by a private corporation for a lucrative contract. Built over Kumeyaay land and history to separate two contested and impinging settler states – the U.S. and Mexico – the border wall is precisely a representation of American hegemony that performatively tries to un-write Native presence, history, and sovereignty. It is a brutal representation of white supremacy clamouring to become reality through Indigenous elimination. Even as lawsuits against the wall are dismissed by settler-colonial courts, ongoing Kumeyaay resistance performatively complicates the U.S.’s claim to hegemonic rule.

The wall comes tenuously and incongruously into being as material fuel for the hallucination that is the U.S. election: a grotesque phantasmagoria of white supremacist nostalgia and cruelty ruthlessly etched onto the land with Black and Native blood, making resistance efforts seem as dauntingly impossible as they are urgent. Part of what Simpson refers to as the limits of Internet activism has to do with the unreality of this phantasmagoria, as both too contrived and too abstracted from the specificity of our spatial and temporal setting.

The particular spatio-temporality from where I am writing is testament to the short memory of American hegemony as a figure of U.S. technological exceptionalism. A mere 60 years old, UC San Diego – itself a jewel of the military-industrial-academic complex – is built on Kumeyaay lands, with the Chancellor’s own institutional residence brutally constructed – in the requisite modernist-cum-colonial-mission style – over sacred Kumeyaay grounds.

I take this seeming detour to acknowledge where I am writing from, intellectually and materially. As most places within the Americas, it was a mere few decades between the overt colonial subjugation of Indigenous peoples in Southern California and their so-called 'assimilation' into the structures of U.S. governance. Native Americans were unilaterally declared U.S. citizens in 1924; the colonial 'Mission Indian Agency' tasked with managing Southern California’s First Nations was terminated (in name only) in the 1950s. Prior to Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. colonisation, this region of the continent was the most densely populated part of North America and the most linguistically diverse. You do not undo such a thick and rich set of cultures and sovereignties in just a few decades – colonialism can only try to mystify and erase them.

Hegemony, in this sense, is the successful deployment of such imaginary representations. As Simpson notes, the spatial imaginary of settler-colonial hegemony is Cartesian space – disembodied systems where only white bodies count, and where Black bodies and Indigenous land only count to be abstracted through commodification or elimination. But there is something interesting with these hegemonic representations: through imaginary means, they are able to exercise real power. Native genocide is real; white supremacist oppression is real. In other words, there is a material technology to these hegemonic imaginations, a logistics, an architecture.

This material dimension is what I am going to focus on here, over four consecutive blog posts, to ask whether something like 'platform urbanism' could be conceived in counter-logistical terms, to theorise an explicitly decolonial Marxism. In practical terms, I hope to offer a view of how architecture might be used as a tool to think through a decolonial platform urbanism, by showing that the relation between sovereignty and territory cannot be articulated without an architectural analysis of how settler space comes to be occupied, alienated, and reproduced. Corporate capitalism systematically alienates labour and land, mobilising and displacing them – and thus destroying the Indigenous contexts from which they are taken. To understand how this happens, it is necessary to understand how a certain architectural kind of knowledge both partakes of and orchestrates the division of labour, and how this knowledge is recursively mobilised to reproduce capitalism itself.

How should we think of corporate capitalism in terms of decolonisation, platforms and architecture? The history of U.S. hegemonic representations of state-capital flows offers a clue.

I found the diagram presented at the beginning of this post (Diagram of The Architectural Center) in the archive of the American Iron and Steel Institute – the United States’ largest metals lobby – while researching the colonial operations of U.S. Steel corporation. To my surprise, the archive contained a carefully curated collection of hundreds of architectural publications, focusing on design innovations from factory to site, compiled throughout the twentieth century as metal corporations sought to keep abreast of technical advances in related fields.

I find the diagram compelling as indicative of a desire perhaps as old as modern architecture itself: the dream of total socio-logistical integration – pointing to the deep histories of Platform Urbanism. The early cyberneticism implied by the feedback loops between 'Industry,' 'Architects & Engineering in Private Practice,' 'Architectural and Technical Schools,' 'Public relations,' and 'Research Laboratories,' all magically coordinated by a new 'Architectural Center,' offers a cautionary tale. As we grapple with the existential need to address multiple overlapping systemic crises – from climate change to a pandemic; from racism to resurgent fascism – the desire for a singular technological fix is palpable and understandable. Enter 'Platform Urbanism'. What could be more enticing than the promise of a universal technological solution to the mess we are in?

The Architectural Center is a fable and a forewarning for this urge, this hope, this expectation, this desire, this promise. But instead of a redemptive fix, I would submit that it represents the enduring nexus between capitalism and colonialism as semiotic and material formations that are reproduced through techno-cultural discourses and practices like modern architecture. 'Modern architecture' is here understood as an instrumental capitalist practice in the reproduction of settler-colonial space and subjects. Its key operation, when deployed through projects like The Architectural Center, is to alienate embedded, embodied, and tacit knowledges and materials for construction through conventions of typology, engineering, and other normative legal standards such as building codes. Extracting, isolating, or disentangling local or customary arrangements of use, property, and construction, these formal conventions are architecturally inscribed in subjects, materials, and places, thereby encoding within them the hegemonic system in which they will be mobilised and for which they have been designed to perform. Bodies, knowledges and materials then become commodities that circulate in markets, in a self-reinforcing structure driven by capitalist competition which tends to reproduce the system as a whole. In this particular context, the reproduced 'whole' is the imaginary of U.S. exceptionalism and its real structures of state administration.

Importantly, the processes described above are not ruled 'from above' by a singular authority, corporation, class, race, or state. Rather, we must understand them as the historical results and technologies of settler colonisation; the granular architectural components of capitalist territoriality that texture and pattern capitalist hegemony as it operates through and on settler colonial space.[2] In other words, it is a view of architecture as a tool of 'impersonal rule' that foregrounds the ways in which space is operationalised as architectural, by the 'science' of modern architecture, in settler-capitalist contexts. As Chandra Mukerji and others have noted, this (material and cognitive) architectural 'texturing' of territoriality is key for the impersonal rule that is the signature of hegemonies. When aggregated into cities and regions, this texture becomes infrastructural. The way in which architectures and infrastructures are integrated as fungible systems is through logistics, which describes their operations, regimentations, administrative or managerial modes of control, and their material requirements. Accordingly, this gives infrastructures a kind of 'logistical power' to shape cognitive and material worlds without the need for direct or overt political domination.[3] Its constitutive operations, however, are architectural, particularly when it comes to the inter-scalar integration of labour and materials, meaning that sovereignty always operates at some level of – and dependent upon – a kind of 'architectural power' that modern architecture precisely sought to rationalise as a universalising set of professional and cultural conventions.[4]

But how did we arrive at a discourse of modern technology in architecture and urbanism that could so effortlessly discount the colonial foundations upon which it was built? Indeed, it was precisely around the time that The Architectural Center was being theorised that Native American sovereignty was being most radically internalised within U.S. structures of government, through either assimilation or termination. To answer this question, we have to zoom in on what is the single most important technical operation performed by platforms: the recursive consolidation of difference that takes place when data points are harvested and then reified as images, plans, or visions of a certain kind of 'totality,' such as a building, a profession, the city, or corporate capitalism. This consolidation takes the form of a commensuration: distinct parts (agents, variables or events) are summed up and turned into imaginary but functional wholes.

The relation between parts and wholes is key to theories of hegemony, connecting as it does questions of logistics – what element gets to be a part of what whole; how does it move in a material sense? As well as questions of meaning: what belongs where; How do elements within a system acquire a particular sense through their position and operations within that structure?

I want to think of 'platform urbanism' as a contemporary version of this problem, which is as old as modernity itself. But, rather than assuming modernity as a singular agent or ontological reality, I will ask in what ways it both presupposes colonialism as an ongoing structure of domination, as well as in what ways we might think of platform urbanism with its dialectical opposite: an anti-systemic decolonial tool to design the pluriverse – a world where many free and autonomous worlds are possible.[5]

In other words, can platform urbanism be thought of as a potential tool for an emerging decolonial Marxism?

Comments