Mierle Laderman Ukeles laid out a conceptual distinction between what she called two basic systems, namely 'development and maintenance,' in her 'Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969!'[1] Development, she writes, is concerned with 'pure individual creation; the new; change; progress; advance; excitement; flight or fleeing' while maintenance is concerned with actions that 'keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight.' In contrast to the value attached to acts associated with development, maintenance work, which takes 'all the fucking time,' is disregarded as part of building culture. Her artistic solution, outlined in the second part of her manifesto, is a plan for a show titled Care, which would 'zero in on pure maintenance, exhibit it as contemporary art.' The show would focus on three spheres of maintenance work – the personal, involving ordinary household chores elevated to a work of art by virtue of their performance in a museum; the general, involving interviews with the public about maintenance work; and earth, which would focus on rehabilitating refuse materials that would be brought to the museum, thus turning the museum itself into a site of repair and maintenance for the city itself.

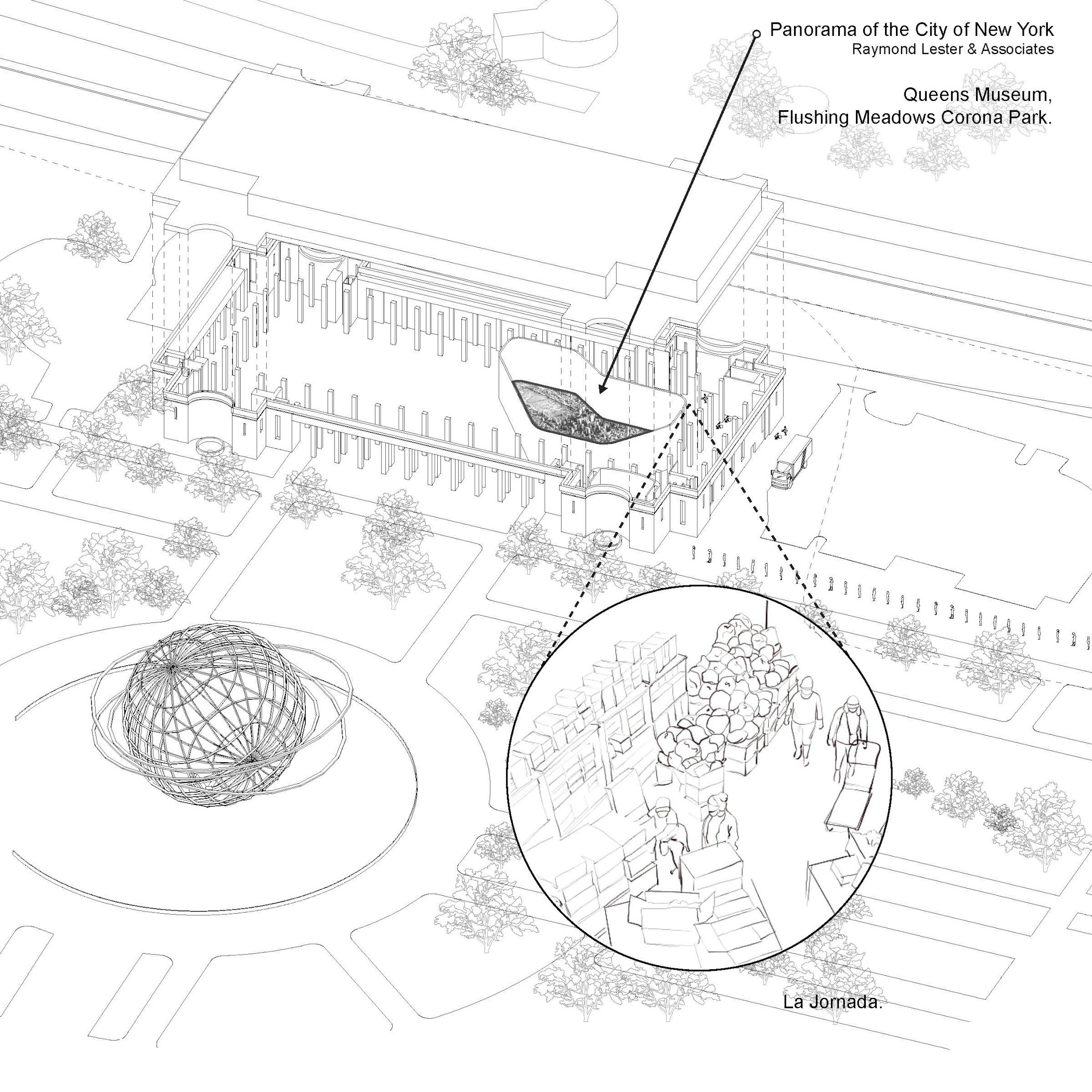

During the summer of 2020, the Queens Museum turned into precisely such a site, opening a section of its building to host a weekly food pantry, in conjunction with a local organisation, La Jornada. From serving the community as a space of reflection on creation and progress, the museum became a space for the basic maintenance of the community in a time of extreme crisis. As other systems became paralysed, one might say the museum became a quintessentially performative space, physically drawing a network together into place. Word of the pantry spread through the La Jornada network as well as intense outreach work done by the community organiser at the Queens Museum, Gianina Enrique with a group of volunteers drawn from La Jornada and a non-profit group, Together We Can Community Resource Center. Food received from federal relief programs and through charity organisations is brought to the museum's side entrance and packed in a high-ceiling hall that once led to artist studios.

As in Mumbai, Gia and her team work the phones, reaching out to families who cannot come to the museum-turned-pantry to collect their packages of produce and groceries and arranging for people to drive over and deliver the packages. Most of the distribution takes place on site as families line up outside and wait patiently. The museum organises outdoor, socially distanced art activities for the kids who come along with their parents during the long Covid-19 summer with its void of activities. These gatherings are organised, quiet works of maintenance art in Ukeles' terms. [2]They are also public acknowledgements of systemic failure on the part of the state to extend care to its citizens in need. Feminist political philosopher Nancy Fraser points to care-work as manifesting a contradiction in the reproduction of capitalist systems – at once vital to social reproduction and disavowed, thus rendering care work inherently unstable.[3] How then could certain public institutions such as the museum become a site of care work, work that is normally relegated to private and domestic spheres? As blue-collar waged work evaporated during the Covid-19 lockdown, the lines between public and private were also arguably erased. As valued, wage labour was no longer available, volunteer labour in food pantries and other sites meeting basic needs began to fill the voids in time created by the absence of wage labour. When prices could not be met due to the absence of wages, acts of solidarity began to determine what was valuable and what needed to be cultivated. Newly emerging networks offering solidarity to neighbours in need rapidly became the substance of Covid-19 urbanism, deploying spreadsheets and Slack, Facebook, Signal and Instagram to reinvent unwaged and undocumented residents as potential users who needed to be connected to platforms offering basic goods and services.

The museum as pantry is one such site of the reinvention of the urban dweller and hustler as a user of urbanistic platforms. Can the public function of the museum ever return to its narrow imagining of culture as framed and consumed? In the performance of the pantry, what is the value form being shaped? How is the beneficiary imagined? As a user or co-creator and participant in a new culture of solidarity? Imagining the pantry as a manifestation of a platform mentality we might ask what is being extracted in this move and who benefits? While the museum, as public institution, is crucial for generating the conditions for these new forms of sociality, the emerging social forms are themselves based on a non-transactional form of exchange, but exchange nevertheless. If platform is the ultimate seat of transactional exchange that enables collective life in a digital world, the museum answers the existential question of where this collective life is taking shape, however fugitively.

La Jornada of the Queen’s Museum, New York City.

Comments